Here the Credit Bank shows its face, explains how it all began… and says thank you to:

My name is Johannes Burr; I am, so to speak, the face behind the Credit Bank, that is, the initiator of the Credit Project and the outfitter of the CREDIT Suitcase.

Furthermore, as the project’s first lender, I am also part of a long chain of other lenders and borrowers, a chain that already began long before my time, somewhere, sometime, with someone I do not know – and it will continue long after me. Because as a credit bank, I am also a borrower, I must receive trust – in the sense of the Latin “credere” (believe, trust) – from others if I am to be able to set something out in the world myself. No dough, no go, as the saying goes… And here’s the spoiler: the best “dough” is of course not that which is borrowed, i.e., the credit, but the gift given. That also played a major role in this project. But more about that later.

So how does one become a credit bank? How do you put yourself in a position to be able to give something interesting and “valuable” to others, which also potentially puts them in the same position? How do you set a creative snowball effect in motion – not just for yourself, but also for others?

Without a doubt, there are many ways to get there. My own route will only be briefly reported here:

Once, I studied art. It is often said that you only become an artist if you have studied art. So that’s why I’m now an “artist” and I do “art”, whatever that means. I didn’t learn how to do anything else. Actually, I didn’t learn anything at all.

What happened was: What do you do when you are in your early twenties, you don’t know what you want and you have landed at a so-called “Free University” in order to find out what studying and life in general is all about, and then you discover that the place is anything but “free”? That was in the early 1990s, the time when student protests took to the streets and occupied the Berlin state parliament, protesting, among other things, against tuition fees and calling for more autonomous studying and teaching. And ultimately I too wanted to be able to redefine and shape, together with others, the content and form of my studies myself. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, there was a sense of something in the air; something like a great promise for change and a new beginning, a fresh wind of change. However, like many others, in my naivety I hadn’t expected to meet so much academic mustiness and rigid thought traditions in a place that called itself the “Free University”… So what could I do?

The art academy seemed to offer one possible path: Fine Art, with the freedom to experiment in any form! Once you got in, it was said, you could do whatever you wanted. Fine art it was then!

With the entrance examinations, however, the inconsistencies started again. One professor only wanted to see simple linear nude drawings, the other, as many lines as possible, a thicket à la Giacometti…. It seemed more like a game of roulette as to which taste in art would preside in the respective examination board…

Somehow, however, I was lucky. And once you were in, you actually could do almost anything, even nothing. Or better: NOTHING – in capitals, a big, loud, busy, important NOTHING. A real question mark. And so I started doing nothing, producing a lot of nothing, more and more question marks, even after my studies. The transition from the art academy to the art system is a fluent one, always looking for money to be able to do even more nothing. Because without money, even nothing is not possible.

At some point, towards the end of my art studies, when I realized that I still did not know what Nothing is or how to not only do Nothing but also become as financially successful as possible, I came up with an idea: Why not just make a film about money without money, which would make a lot of money?

A short script emerged: about a banker who mysteriously disappears one day after falling out of a window and makes some interesting discoveries as a result.

A second try was the short film “Empedocles in Berlin“, which tells the story of an unemployed musician who drifts through Berlin like a kind of “living” money; connecting, seemingly randomly, stories and people and collecting stones in his empty cello case. However, none of these projects made any money…

Actually, it was about something else. Namely, how can anyone make “art” at all without simultaneously asking about “money”: What is money? Does money perhaps have a lot more to do with the creative process than might appear at first glance? Does our focus on “earning a living” and “making money” perhaps distract us from more important questions, such as how money is created and what its essence is?

Much had already been written about money. So I read books, watched documentary films. And asked a lot of people. I encountered many different opinions and points of view. But one thing gradually emerged, a startling discovery:

Even money comes into being these days – like art – from nothing, it is itself a “positive nothing”: nothing comes out of nothing… That’s why bankers use the term “fiat money“, because it gets created, just as God created the world out of “nothing” according to the Bible: “Fiat lux – Let there be light! And there was light…”

There was nothing; out of the creative act came a nothing; a positive nothing, an embryo, a germ of a thing; and, permeated by light it begins to form, to shape itself, until the formation of light appears.

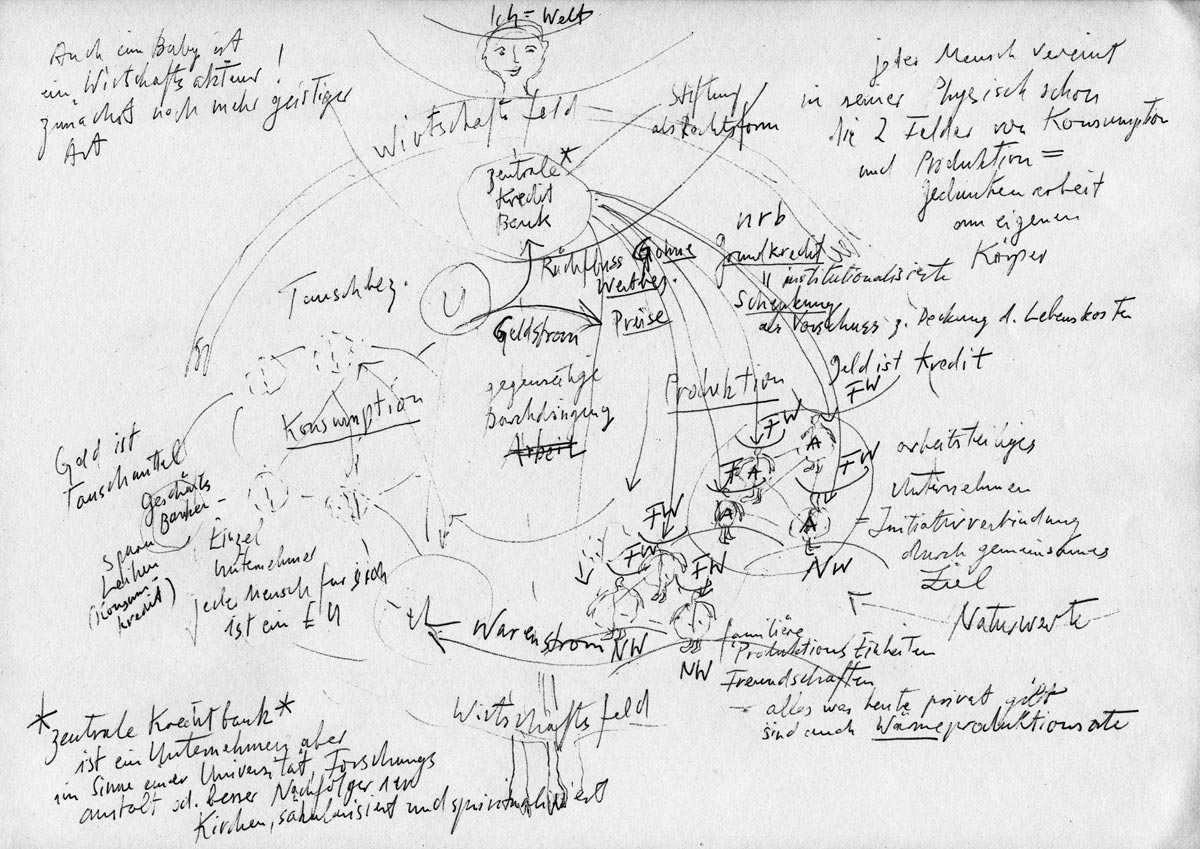

In the same way, a bank – usually a central bank – creates money out of nothing by means of a legal act. A simple accounting trick brings money in the form of a debt-credit pair into the world. The debt remains in the bank’s books. The loan, however, goes out into the wide world as a certificate of entitlement, seeking capable people who want to harness its potential to create something new for which there is a need. That is how money comes into circulation.

In circulation, however, money apparently changes its face; it is no longer credit money but exchange money. As such, it facilitates barter transaction: one may buy something with it, another wants to sell something for it, and the two – hopefully for mutual benefit – engage in business… Ultimately, however, exchange money always sends a signal back to the economic cycle that what has been bought should be produced again. Only in this way can supply and demand take place in a social, labour-dividing context, in which they can be sensibly regulated and coordinated via pricing. On the one hand, money allows us to meet our needs as consumers through mutual exchange, and on the other hand, it allows us to develop our skills as producers and to practise them in a productive process tailoured to the needs of others.

After making such a discovery, what could be more logical than deciding to simply switch sides and become a banker? As a needy artist, why go chasing money for your own “negligible” projects when instead you could simply create and distribute money as a bank yourself, thereby enabling others to also create as much “positive nothingness” as possible?

Anyone can be a banker. Because if both art and money are created out of nothing as “positive nothingness”, then they must be something very akin, if not the same, insofar as they both relate to our creative abilities, to our creative potential: money as credit enables the training and realization of abilities. As exchange money, it connects us and establishes a balance between dependence and need on the one hand and creativity and productivity on the other. And art is the result – or, more precisely, the process of creating, and creation itself. However, while each of us has skills and potential, money is often lacking. So why not make art out of the process of creation of money and monetary relationships?

So that’s how the idea for the Credit Project came about. Between 2006 and 2012, I traveled the world with the CREDIT Suitcase as a mobile credit bank, always looking for a new borrower. That was not always easy, not everyone wanted to take on such a loan, because it meant taking responsibility for it (which I got rid of myself – at least for a while!) But, ultimately, someone could always be found, and that’s how, in six years, a total of seven Chain Films came to be produced in different places.

However, within the current legal situation, it is not possible for me – even with all the artistic freedom I have – to simply create money as my own credit bank. So how did I get the CREDIT Suitcase, camcorder, tripod, and everything else? How did I manage to stay afloat over the years, traveling to my borrowers, buying us food, sleeping in a bed under a roof, without having to beg in the pedestrian zone?

That brings us to another important and very last question:

What actually happens to the debt in the bank’s books? How does money find its way back to the beginning of its cycle? How can the debt be repaid in such a way that the money disappears into nothingness once again?

Anyone who has taken out a loan must repay it, of course, usually with interest and compound interest. But does that really “neutralize” the money that was created out of nothing? Does that close the loop? How exactly do we deal with this question in our current economic system?

As an artist, I know that new forms can only emerge when old ones are destroyed. In every creative process, something has to be led back into chaos so that a new form can emerge from it. So how does this apparently necessary third transformation take place when credit and exchange money return to their origin, which was in the act of creation out of nothingness that was performed by the bank?

It seems that we have not yet really found a satisfactory solution at the societal level to this central question. A lot of money is indeed destroyed by wars, speculation, any form of artificially created scarcity, environmentally-destructive technology such as nuclear power, trips to the moon and Mars, etc. But could the apparently necessary “neutralization” of money once created not also be undertaken in a productive way? Does it always have to drag our livelihoods with it into chaos and destruction?

In his magnificent book, Debt: The First 5,000 Years”, David Graeber also investigates this question and comes to astonishing and fundamental insights.

And his answer is also: No. Because we can still give! Graeber points, for example, to the custom of forgiving all debts in a society every seven years (sabbatical year), which is enshrined in the Jewish faith. But does not every form of private, or, above all, “institutionalized” giving represent a kind of act of neutralization in which, on the one hand, the money given away is liberated from its original coercive relationship with debt, i.e., it is neutralized, and, on the other hand, the recipient is simultaneously given the capacity to create something new in complete freedom?

But just as bankers never own the loan money that they create and distribute, but only manage it in a fiduciary manner, I could also only pass on the CREDIT Suitcase as something that I did not own but had been given in some form, by others: Without free giving, no free giving; without free support, no creative processes; without trust in a positive nothingness, no free development…

(All the material published on this website is therefore also licensed under a Creative Commons license and can be freely accessed and used by anyone).

So many people contributed directly to the success of this project by making tangible and intangible donations that I would like to express my gratitude to them on a separate page!